Water of the Flowery Mill

- Year

- 2002

- Duration

- 15:00

- Category

- Chamber Music

- Instrumentation

- alto fl/gtr/per/vn/va/vc

- Location

- Manhattan, New York

- Dedication

- to William Anderson

- Commission

- Composers Guild of New Jersey, annual commissioning endowment fund, 2002

- Purchase

- Theodore Presser

Description

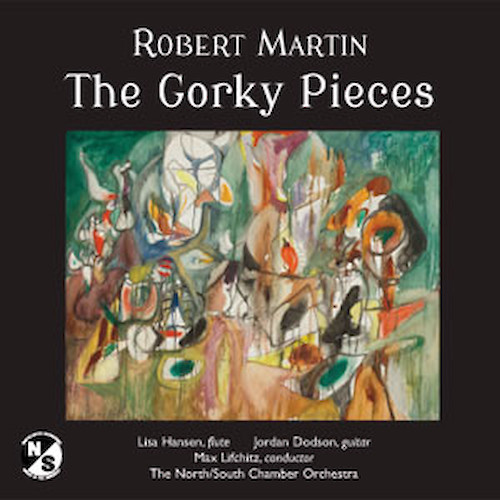

Martin’s sextet takes its title from the painting by 20th century artist Arshile Gorky. The 15-minute work was made possible by a commission from the Composers Guild of New Jersey and dedicated to William Anderson who premiered it with The Theatre Chamber Players of Washington, DC.

The Background Structure in Water of the Flowery Mill

Sometime after I had arrived in New York in the mid 70’s, a number of us went to a new music concert. One of the pieces that was performed was for solo piano. It was like an atonal version of Ravel’s Gaspard d’Nuit, with a never changing bell-like repetition in the high register. Afterwards we met the composer, whom we all knew already. Someone turned to me and asked what I thought of the piece. I had a reputation for being rather critical of the music we heard, and everyone (including the composer) turned to listen. I said that I would change nothing in the piece at all (everyone was pleasantly relieved). But then I added that I would change nothing except to transpose the last chord up a half step. In other words with this revision, the tolling bell throughout the piece would become the leading tone moving to the resolution with an overwhelming amount of force. The static bell, so beautiful in Ravel, would now have a new energy. As far as I know, the composer did not take my suggestion. In fact, I believe that he thought it was one of the worst suggestions that he had ever heard. He felt that it would destroy the vivid connection to Ravel which he had struggled so hard to preserve.

This story illustrates a basic tenet of mine about music—it should move. One of the arguments made against me in those days was that music should start at a location, and then return to that same location just as the models of the Classical Period, (however, see Beethoven’s Opus 101 where the beginning goes to a different end). I cannot offer any empirical argument for why I feel that it is all right to deviate from these Classical models. I do admire them and hold them in the highest esteem. But that was then and this is now. Now, I believe that music should move, and when it leaves its starting point, I do not think that it must always return. Perhaps I can say it like this--once music gets somewhere, I’m so grateful for this great achievement that I don’t care if it makes it back again. The background notes of Water of the Flowery Mill do not return to their starting point.

The first actual background note is the “A” in the cello in measure 12, although I believe that the “B flat” that precedes it is a foreshadowing of the “B flat” in the cello in measure 534 (also a background note). In addition in measure 11, the guitar has a “G sharp” and an “E.” Please keep in mind that this piece is not only about background notes, but also about intervals. The major third is the most important interval in the piece and the guitar tells you that here. And the importance of the major third is further reflected by the expansion of the minor third to the major third in the viola and cello.

Throughout the piece, major thirds make a vast number of appearances. The preparation for these arrivals is too extensive to catalogued here. I will mention only one. In measure 520, the guitar plays “A flat” (which should, of course, be spelled “G sharp,” but is not because of the “G natural” just above) and “D,” which resolves to “A natural” and “C sharp” in the same measure—dominant (formed by the tritone) to tonic (formed by a major third). Nothing could be more straightforward, and I delight in placing such an obvious—even trite—resolution in plain view for all to hear. After all, the best place to hide something is in plain sight. So, temporarily at least, the piece has returned (over 500 measure later) to its starting point—the “A” in measure 12 has returned to the “A” in measure 520, and this is emphasized by the dominant tonic relation in the guitar’s “G sharp” and an “E” in measure 11, as well as the tonic to dominant relation of the tritone to third in the guitar in measure 520.

We pass a great deal of music to arrive at the Affettuoso in measure 186, a section that nudges the dominant-tonic relation slightly forward through the often-smudged layers of paint. The emphasized tonic note is the “F” in the alto flute in measure 188 to 189. However, the flute backtracks to the initial note “A” in measure 194 to 195, and echoes this in measure 196. In measure 197, there appears a cluster of three notes that suggest a tonic. These are “A sharp,” “B” and “C sharp.” Obviously the suggested tonic is “B,” and that becomes the next background note. Can someone hear this note as a background note within this cluster high in the string harmonics—I think not. But I do not believe that musical structures must obey the same rules that buildings built by architects obey. Here, a foundation note is at the finial of the steeple. How is this possible? This is possible because this is music. And I do find it dull to belabor the bass, but doubtless most composers disagree with my view on this.

Finally, the alto flute plays an “E” in measure 201 to 202. This signals that we will leave (temporarily) the world of somewhat clearly suggested dominant to tonic relations (as another way of interpreting the arrival to the major third), especially because this note suggests the minor seventh of the dominant.

Don’t miss the “A” in the violin in measure 209, which is the lingering vestige of the initial background note “A” in measure 12. And notice that, against it is placed a “C” and an “A flat” in the cello which foreshadow the cello notes starting in measure 551. That means that this particular measure is an “alpha and omega measure.” I am fond of these types of unusual and unconventional intersections—the beginning and the end intersect in the middle in two ways.

Come forward to the Declamando section in measure 242, where the cello quickly arrives at an “F sharp.” It is another point of arrival to a major third (are you cataloging all the different approaches?) Now the background notes are as follows: “A” “F” “B” “E” “F sharp.” If you are sharp at constructing all interval rows, then you have probably already guessed the next note. That’s right, it is “G.”

In measure 283 you find the “G.” But you also find the same important pattern as so often occurs elsewhere—the suggested tritone dominant resolving to the suggested tonic. The “G” and “C sharp” foreshadow the same notes in the guitar in measure 520, and the “C” and “A flat” foreshadow the same notes in the cello in measure 551. This is another type of strange intersection. This is also a false ending (there is almost nothing in Beethoven that is not in Hadyn).Finally, we reach the “G” in the guitar in measure 520, which adds a “D” and resolves to “C#.” You should not be surprised to see an “A” here as well (remember the initial “A” in measure 12? But music must move, and as attractive and neat as it would have been to complete the piece on this “A,” we must add the “B flat” in the cello in measure 534, then the “A flat” as well as the “C” both in the cello in measure 551. This produces 11 notes of an all interval row as follows: “A” “F” “B” “E” “F sharp” “G” “D” “D flat” “B flat” “A flat” “C.”

Where is the last note, namely “D sharp?” As you probably know by now, the twelfth note of an all interval row is always a tritone away from the first note. For me, this is too predictable a relationship to preserve and reproduce. So, for the sake of artistry, I almost always drop it, leaving a steady stream of undone rows, that, nevertheless make a smooth presentation of both twelve notes and eleven intervals—let someone else pick up the pieces of the dropped notes.You mentioned that you believed that the notes in the guitar in measure 520 existed on the surface level. As I mentioned before, I am fond of strange intersections. Here the background and surface are intersecting. And why should that not be permitted (if only to confound the analyzer)?

I hope you find this analysis useful--I do not. In fact I, myself, am quite bored by this type of dissection, and I feel that others should do it—not me. I’ve already done my share. There is another reason why I have little interest in this type of analysis. It is because there is so much going on that is usually neglected, and I tend to emphasize these aspects that are discussed less and involve much more artistry. Unfortunately, talking about how dissimilar a phrase can become from its neighbor before it loses its connection to that neighbor is not a popular subject in theory classes these days, but I find that topic and others far more interesting. A third reason that I don’t tend to emphasize this sort of analysis is that it carries the suggestion of finality. For me, no single analysis is final. I could find alternative interpretations that would be—I believe—convincing. And just because there are all interval tone rows at work in the back ground, does not negate the tonal nuances that continue on other levels.

Good music is filled with secrets, and to a great extent, it is not for the maker of the secrets always to reveal them. It is for the next traveler to enjoy the excitement of discovering them. Here, one more time, I have made an exception because of your continuous suggestion for years that these secrets do not exist simply because you have not found them. In fact, really this music is like a forest. There are blades of grass that look like trees when viewed up close and trees that look like blades of grass when viewed from far away. And there are all sorts of trees and blades of grass in between these extremes. When you view a cloud up close, it looks like a cloud. When you view it from far away, it looks like a cloud. Wherever you happen to be and whatever your location, all you have to do is stare a little while and I guarantee you that sooner or later, you will see more clouds.

– Robert Martin

Past Performances of Water of the Flowery Mill

| Date/Time | Location | Artist/Players |

|---|---|---|

| 2003-02-15, 8:00 PM | Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts, Washington, DC USA | The Theater Chamber Players (William Anderson, guitar) |

| 2003-02-16, 3:00 PM | Bradley Hills Presbyterian Church, Washington, DC USA | The Theater Chamber Players (William Anderson, guitar) |

| 2003-09-17, 7:30 PM | Aaron Copland School of Music, Queens College, Flushing, NY | Recording |

| 2015-01-11, 3:00 PM | Christ and St. Stephens Church, New York, NY USA | Max Lifchitz, North/South Consonance |

| 2015-01-15, 10:00 AM | North South Recording (N/S R 1063), New York, NY USA | Max Lifchitz, North/South Consonance |